1968 in Europe: Youth Movements, Protests, and Activism

Big Question: More than 50 years later, why are we still talking about 1968? What are its legacies in Europe?

Time Commitment: 90 minutes

Engage and Reflect: Consider these photos and information about 1968 in the U.S., from The Smithsonian Magazine. (17 minutes)

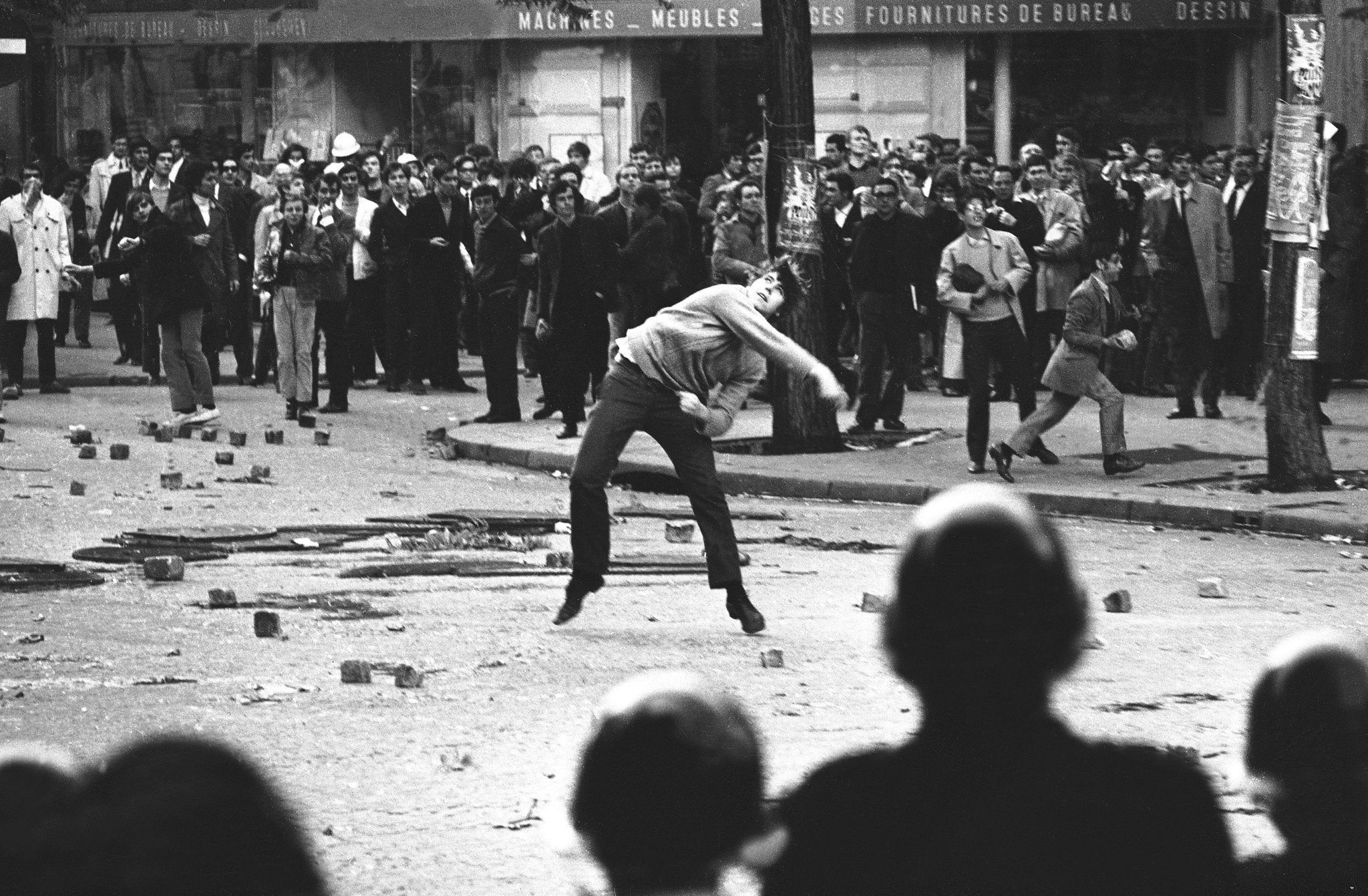

A student hurling rocks at the police in Paris during the May 1968 student uprising. The protests transformed France. Gamma-Keystone, via Getty Images

Why This Matters:

1968 was a year of social and political change across the world. While Americans lived through two assassinations (John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.), the anti-Vietnam war and civil rights movements, the first televised war coverage and civic protests; internationally unrest hit Prague, Paris, Rome, and also Tokyo and Moscow. The world underwent a profound social transformation that would change it for good. Considering the high level of interdependence between historical and social events of that epoch, being informed about what happened in Europe can help gain a critical perspective over what happened elsewhere. Most importantly, the different connotations of the term activism in the European context precisely resulted from the different historical circumstances of that region of the world.

Diving In, Part 1: Introduction to 1968 in Europe

The term “1968” refers to a cluster of events and processes that began in North America and in Europe in the early 1960s (with roots stretching back into the 1950s), reaching an initial high point around the calendar year 1968. This was a period of sociopolitical youth rebellion, a large generation born in post war peace where due to the invention of the television, growing influence of the media would spread information quickly. Additionally, the political concept of ‘Europe’ was brand new, adding to economic instability domestically.

Following the devastation post World War II, the Yalta conference in 1945 re-drew Europe into two blocs: East and West. Western European preeminence was declining geopolitically, giving way to the emergence of two new world powers: US and Soviet. Within these two opposing political directions, European countries were seeking to define their own roles within the recently established entity; the European Economic Community (ECC) as designated by the Treaty of Rome in 1957. One example was French president Charles de Gaulle, who was opposed to furthering the ECC reach in the form of a European Parliament. His position stemmed from equal parts national pride (insisting on French veto power) as well as the perceived threat of greater US political and economic influence in Europe. Yet other leaders showed open support and Europe continued to expand to include Denmark, Ireland, UK, and Norway by 1962.

The major underlying question was would Western free market capitalism or Soviet communism hold sway in Europe? Could a distinct European leadership emerge? With the Vietnam War underway and growing social dissent for the US and France’s involvement, a new Europe was faced with severe internal turmoil. Italy and France were also experiencing strong socialist movements threatening the established order. The Soviets hovered close to the Eastern European border, a reality that advanced interest in the possibility of a united European foreign policy.

In addition, Western European countries moved into a post-colonial era, their former colonies seeking independence by political and sometimes violent means. In France, in the midst of the prosperous ‘trente glorieuses’ epoch, an influx of immigration from suffering neighboring countries and former colonies changed the demographics and the labor market. Such shifts in power and influence, coupled with growth in increasingly diverse populations, characterized shifts throughout the mid-60s in Europe.

Read and Reflect:

Think about Europe today in terms of a world power. What are its symbols, strengths, and/or weaknesses? Did the geo-political questions from the 1960-70’s get their answers? How so?

Diving In, Part 2: 1968 Roots of French Social Activism

Not only was Europe facing a political crisis, social unrest within France was mounting. French maintained a much higher standard of living post-war, accompanied by a strong state. Aiming to reform a rigid, hierarchical French university system, to decry inequalities in capitalism and imperialism as perceived globally and specifically within the de Gaulle government, in early 1968, Parisien students began organizing. In the long tradition of French ‘républican’ governance, it began with informational campaigns and democratically styled ‘Assemblée Générale’ on campuses. Then they staged sit-ins on Paris’ Nanterre and Sorbonne campuses, coupled with protests. They exemplified the generation gap happening throughout the West where defiant young people were finally confronting their elders: the establishment made complacent in the post-war boom. Their spontaneous revolt drew in others who were equally dissatisfied with de Gaulle’s politics, yet came from different socio-economic status and regions. In early May, students took to the streets in great numbers.

View and Engage:

This video edited from the National French film archives (INA) shows the intensity of their protest movement and the strong show of force they met in the Parisien police. Claude Nougaro’s protest song "Mai Paris" (featured in the video) has remained emblematic of the dramatic set of events.

Meanwhile in Brittany, workers at a major factory near Nantes staged a walk-out, and others followed. Workers unions, farmers, and students joined together. By mid-May, social movements spread to other universities and factories across France. At its peak, more than 10 million people were on strike, bringing the country close to a standstill. The protests took hold of French society in such a way that political leaders feared civil war. President de Gaulle dissolved the ‘Assemblée Nationale’ (similar in function to the US Congress) and the national government briefly ceased to function.

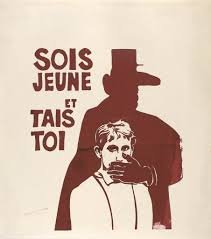

View and Engage: The Street Art of 1968; the Sociology of Signs

The following posters were designed by students in Paris’ prestigious Academy of Fine Arts, and they were widely distributed and hung in the streets as well as made into protest signs for marches.

In this sepia toned poster, the large figure of a member of the police holds their hand over the mouth of a young person. The tagline "Sois Jeune et Tais Toi" means "Be Young and Shut Up."

École des Beaux-Arts

In this red and orange poster, the tagline "Travailleurs français immigrés tous unis" means "Workers - French, immigrant - all united." There are three figures: Francais, Immigres, and an unnamed figure trying to keep the two apart with their hands.

École des Beaux-Arts

In this black and white poster, the tagline "unite ouvriers paysans" means "worker farmer unity."

École des Beaux-Arts

Reflection Questions:

What objects and relationships are depicted?

Which different groups are included in these images?

Can you identify the power brokers of the establishment? (clue: look for the business hat and the ‘képi’ or French military hat)

What signs of oppression can you identify?

As an inclusive social movement, these posters called to unify workers, immigrants, farmers and labor unions, and youth. Such a call to join forces was never before assembled by this traditional, bourgeois institution, nor in the streets. The small capitalist businessman is seen separating workers by their national origins, while the oppressive President de Gaulle (former military general with oversized nose) is silencing the young man.

The next two posters depict the means of struggle. As seen in the above video, strikers used paving stones as weapons to defend themselves against the police.

In this black and white poser, an individual hurls a stone. The tagline,"La Beauté Est Dans La Rue" means "Beauty is in the streets."

Beauty is in the Street

In this black and white poster there appears a large paving stone and the tagline, "Moins De 21 Ans Voici Votre Bulletin De Vote" which means, "Under 21 Years Old - Here Is Your Ballot."

Reflection Questions:

Who is throwing the paving stones? Where?

What number is displayed in the poster? What could its significance be?

Although a protest movement against the de Gaulle government, the 1968 movement was equally a testament to values of ‘la république française; liberté, égalité, fraternité’. Students began organizing using democratic processes and the principles of free speech. In these posters, the paving stone thrown in the street is typified as a heroic public act. In the next poster addressing people under the voting age, 21, instead of a voting ballot (or ‘bulletin’) it is suggested to ‘vote’ by throwing a paving stone.

de Gaulle’s resignation and several political upheavals followed closely. These social reform movements gave rise to more than five years of unrest and had lasting effects on shaping new values and law (i.e. the legal French voting age was reduced to 18 in 1974 in part as a result of these movements). Most notably they laid the groundwork for the European anti-war movement while also contributing to future environmental, women’s liberation, and gay rights movements. Strong in its political roots of citizen involvement in the political process, 1968 followed in the tradition of ‘l’engagement citoyen’ with public protests showing larger solidarity ‘fraternel’ across diverse groups. Citizens were largely united against perceived negative effects of the government in power.

Reflection Question:

Compare the ideal of a heroic activist today with that of France 1968. Who are they? What are the causes they defend and why?

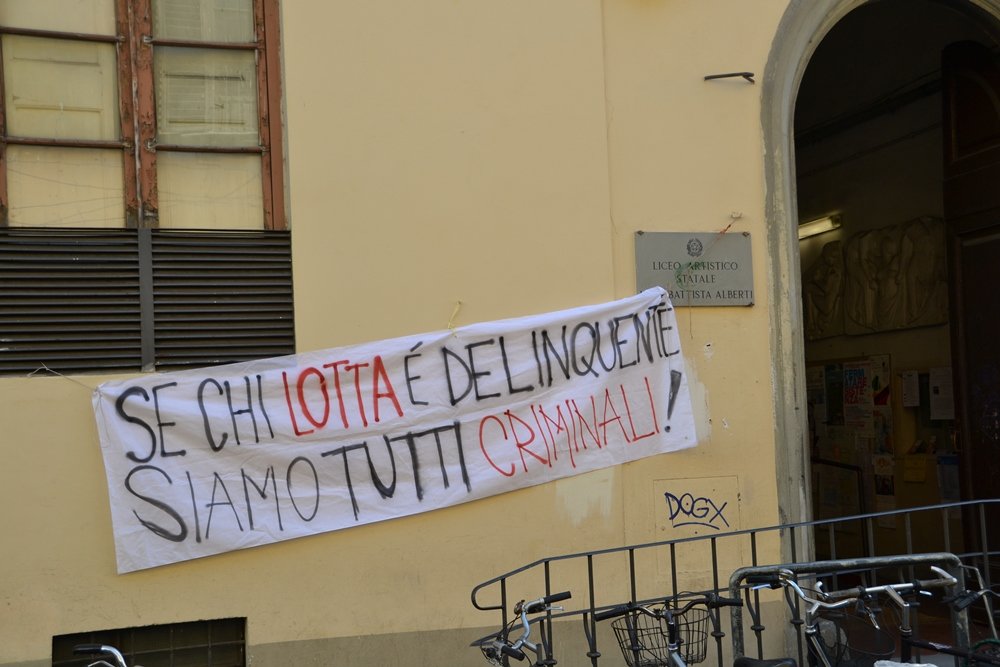

Diving In, Part 3:Occupied Social Centers in Italy

The social center movement in Italy began in the 1970s when groups of young people (students, unemployed people, etc.) reclaimed urban spaces by squatting and occupying empty buildings.

Dr. Valeria Pecorelli defines social centers as opportunities for people to come together to express their anti-capitalist political ideas and oppose the neoliberal model. At the same time these spaces where people gather offer social alternatives inspired by the desire to create collective spaces that are autonomous, self-managed, supportive, alternative, radical, rebellious, and free from the logic of profit.

In addition, Dr. Carlo Genova interestingly translates the Italian expression “social centers” as “political squats” and defines them as “groups who occupy buildings to develop political, social and cultural activities potentially directed also to an external public.”

The first wave of centers emerged amidst the shift from industrial to flexible forms of production that left vacant large stretches of the cityscape in urban centers around the world. In Milan, industrial production gave way to an economy based on the finance, fashion, and services industries that brought with them high rents and low wages. These forms of inequality seem to be an inevitable consequence of industrialization and have been observed in various countries around the world since the 18th century. Look at this union card from from 1894 titled “The Condition of the Laboring Man at Pullman” below:

View and Engage: What is happening in the image above and who are those two individuals ? How would you describe this kind of drawing and what was it meant for?

What the union card above communicated pictorially was the need to take action (literally, to re-act) against an economic system that crushed workers. Fast forward to almost a century in the future, people participating in social centers in Italy shared a determination similar to the one the image above sought to incite: to urge citizens to take back what neoliberalism had taken away. In particular, they believed that the working class had to be autonomous and independent from the capitalistic organizations of labor and society, and that it also had to be independent from the existing party system. The first-generation social centers came to a decline by the end of the 1970s, a decade of political and social turmoil called “Years of Lead.”

Between the mid 1980s and early 1990s, social centers were revived and started spreading all over Italy. By 2004, over 250 social centers had been active over the years, from large buildings like Rivolta in Marghera (outside of Venice) to small spaces in southern Italy. The first social center, Leoncavallo, was occupied in Milan in 1975, and like many others, has been closed and reopened over the years due to police pressure. The unexpected resistance of the occupants to the evacuation of the Leoncavallo squat by police in 1989 was extensively covered in the media and made Leoncavallo a symbol of all social centers in Italy.

Reflect and Engage: We are likely all familiar with scenes from protests and demonstrations, and we may have even participated in one. Protesting is most effective when signs are used. Just like the satirical drawing from 1894 above, signs communicate powerful messages by means of brevity, immediacy, and symbols. Working in pairs, if possible, create a sign to be used in a protest against the evacuation of a social center. You may find it useful to consult this website.

In the 1990s, social centers in Italy continued having conflictual relations with state institutions and developed a distinct collective identity and solidarity. Defined as they were by common traits (illegal occupation of disused buildings, self-management, social centers as a social aggregation venue for the squatters, self-financing), there were also important differences among social centers especially in regard to their ideological orientation (anarchist, autonomous, communist, non-ideological) and their activities, whether political and/or countercultural. About this last point, social centers proved to be fertile places where culture, particularly alternative expressions of culture, could flourish and spread. Operating outside of the coercive realm of corporations and the state, social centers provided spaces for a variety of activities: concerts, nightlife, art installations, political meetings and conferences, radio and TV broadcasting, and spaces for activists to organize. By 1998, roughly 50% of the social centers entered into agreements with local governments or private landowners and many of them are now supported by political parties.

View and Engage: Now, observe these banners displayed by social centers in recent years around Italy. Is this activism?

"More benches, less shop windows."

"If those who fight are criminals, then we all are!"

Page Completion - Outcomes:

Now that you have completed this page and the readings, videos, and activities within it, you should have strengthened your ability to:

Grasp how ideas of social activism, volunteering, and community engagement are differently nuanced in different places due to their specific social, historical, political, economic aspects.

Understand and contextualize concepts of activism and community engagement within European culture.

Learn about specific examples of how EU citizens, individually and collectively, have achieved social change since the late 60s.

Please share feedback on this page by taking this 5-question survey. Thank you!

Next: Is social change only a consequence of activism or can it occur in other ways? Does grassroots organizing make change happen?

Citation for this page: Grazioli, B., Carnine, J. & Brandauer, S. (2020). More than 50 years later, why are we still talking about 1968? What are its legacies in Europe? In E. Hartman (Ed.). Interdependence: Global Solidarity and Local Actions. The Community-based Global Learning Collaborative. Retrieved from https://www.cbglcollab.org/1968-in-europe-youth-movements-protests-and-activism

Further Reading

https://www.amazon.fr/Beauty-Street-Visual-Record-Uprising/dp/0956192831

Citation for this page: (forthcoming)

Citations:

CVCE. (n.d.). Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (Rome, 25 March 1957). Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://www.cvce.eu/obj/treaty_establishing_the_european_economic_community_rome_25_march_1957-en-cca6ba28-0bf3-4ce6-8a76-6b0b3252696e.html

Membretti, A. (2007). Centro Sociale LeoncavalloBuilding Citizenship as an Innovative Service. European Urban and Regional Studies - EUR URBAN REG STUD. 14. 252-263. 10.1177/0969776407077742.

Responding Together. (n.d.). Rivolta Social Centre. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://respondingtogether.wikispiral.org/tiki-read_article.php?articleId=91

ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Flexible Production - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/flexible-production

The Condition of the Laboring Man at Pullman. (1894). [Illustration]. Retrieved from http://www.gompers.umd.edu/Pullman%20Cartoon.htm

Twombly, M., & McDonald, K. (2018, January). A Timeline of 1968: The Year That Shattered America. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/timeline-seismic-180967503/

wikiHow. (n.d.). How to Make Protest Signs. Retrieved May 19, 2020, from https://www.wikihow.com/Make-Protest-Signs

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-a). Decolonization. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decolonization

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-b). European Economic Community. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Economic_Community

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-c). May 68. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_68

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-d). Trente Glorieuses. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trente_Glorieuses

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-e). Voting age - Wikipedia. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voting_age

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-f). Yalta Conference. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yalta_Conference

Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.-g). Years of Lead. Retrieved May 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Years_of_Lead

Videos and pieces cited within the videos:

Dickinson en France. (2020, May 11). Paris, May 1968: [Video file]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O443pN5P8JA&feature=emb_logo

HarvardX. (2018, July 16). Pros and cons of neoliberalism [Video file]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t41rFqVpB1I