Sustainable Actions & Communities

Big Question: How do my actions connect to sustainability and how have my behaviors been shaped by my identity, culture, frame or position?

Time Commitment: 75 minutes

Personal Reflection: How do I feel like I contribute to sustainability initiatives as an individual? How is the community around me contributing to sustainability initiatives as a collective?

Engage: Write three things that you do regularly that you would consider to be sustainable behaviors.

Why This Matters:

Meaningful societal change begins with individual change. One cannot do for a community what one cannot do for one’s self. Sustainable behaviors at the individual level are often seen as meaningless as it’s often difficult to map them into the larger-solutions context. Individual behaviors create the foundation for action in social, economic, and environmental sustainability, and potentially guides our ability to work with one another to make life-affirming decisions. In short, it is a matter of aligning our day-to-day behaviors with our well-stated values that will result in greater sustainable community action (Pappas & Pappas, 2015).

Communities and cultures are shaped by the behaviors of those within them. Behaviors are shaped by knowledge, experience, identity, culture, and positions of power (or lack thereof). When working to create positive change, it’s important to consider these elements at the individual and community level to best understand the why to ensure the what lasts.

Reflection Question: What matters most to you? Why did that selection rise to the top for you? Why do you think you more easily do the three sustainable behaviors that you previously identified?

Diving in, Part 1: We all can play a role in reducing the impacts on the environment, but that role may be defined by accessibility, culture, traditions, beliefs, or knowledge. Conservation strategists suggest that to maximize emissions reductions, efforts should focus on the highest impact behaviors, rather than presenting an overwhelming suite of options. Rare published that without making dramatic lifestyle changes and in the absence of sweeping new policies, reasonable, individual actions could nevertheless have a measurable, substantive impact on reducing emissions. Their report, Changing Behaviors to Reduce U.S. Emissions: Seven Pathways to Achieve Climate Impact shares these seven high-impact behaviors. • Purchase Electric Vehicle • Reduce Air Travel • Eat a Plant-Rich Diet • Offset Carbon • Reduce Food Waste • Tend Carbon-Sequestering Soil • Purchase Green Energy

Question for reflection: Review Rare’s Report. Which of these 7 carbon-reducing behaviors is most accessible to you and which one is least accessible to you? How would these recommendations change if applied in a global context to be more inclusive of people in any community or culture?

Question for application: What is my personal ecological footprint and how does that compare to others? How is my home nation different than other nations? Why does this matter?

Via https://www.footprintnetwork.org/our-work/ecological-footprint/

Review and Engage: The Global Footprint Network is the leader in the creating metrics, insights and tools to calculate your ecological footprint. Recognizing that an ecological footprint is not the same thing as a sustainability assessment, the Global Footprint Network prides itself on long-term, science-driven data from around the globe that compares human demand on nature against nature’s capacity to regenerate. The footprint calculator is available in 7+ languages.

Calculate your Ecological Footprint

Conduct a pre/post analysis of an experience in your life where you think your ecological footprint changed (living at home vs. college, living in U.S. versus another country, travel abroad etc.) What behaviors changed for you?

Diving in, Part 2: What roles do identity, culture, or position of power play in adopting sustainability behaviors?

View and Engage: Our behavioral choices are not always our own. Infrastructure, wealth, access, culture and traditions can play a role in the options available to individuals around the world. Watch these two videos for comparative analysis.

Copenhagen, Denmark Video

Nairobi, Kenya Video

These videos tell stories of sustainability in urban environments in two very different ways. Denmark is a wealthy country in the Global North and Kenya is a lower middle-income country in the Global South. Each have a colonial history and legacy; one benefitted from it, and one did not. It could be easy to compare the two videos and say Denmark is more advanced and Kenya is behind, but these are overly simplistic interpretations. How might these videos look different if the Denmark video was made by Kenyans critiquing energy consumption and wealth accumulation in Denmark? And what if the Kenyan video was in the voice of Kenyans highlighting their own practices and beliefs as they relate to sustainability?

If we dig deeper, we should be asking questions about who an expert is and who creates knowledge as well as who has agency. In the Copenhagen video, carbon neutrality is something Danes are taking collective action on. Danes are driving these decisions. In the Nairobi video, Kenyans are beneficiaries of sustainable water and sanitation projects. Who created these videos? Who are the intended audiences? Where does the power lie in these stories? These videos help illustrate the complex role our position in the world, where we come from, frame of reference and who tells our stories – us or other people – can shape and influence our behaviors and actions around sustainability.

Question for Application: When and how have behavioral practices changed in your life and where those changes driven by culture, power dynamics, infrastructure etc.?

Photo credit: Culture, Local Life and Local People “Aboriginal students commuting to school,” Uluru, Australia, by Marguerite Adams, Dickinson College ’18

“I became a daily cyclist in Copenhagen [Denmark}, a city that was designed for people and sustainability. I was then excited to be a more avid cyclist on campus and in the community of Carlisle, PA.” US Study Abroad Student, 2018

"On campus [in PA], I regularly practiced sustainability behaviors such as composting, reuse, walking/biking, and eating less meat. I took many of these practices home to my family in L.A. and we worked together to reduce our footprints during the COVID quarantine and beyond.” US College Student, 2020

“A semester in Bhutan helped me appreciate food access in the United States. During my time abroad, we could only access local, seasonal foods. There was no choice. It was interesting to return to the options in the US while trying to balance my footprint.” US Study Abroad Student in Bhutan, 2017

“Being in a water scarce area of Cameroon, my host family helped me work towards washing less laundry and air drying my clothes. I had no idea how much I was over washing my items. It was rewarding to share this with friends and family in the U.S.” US Study Abroad Student, 2018

Review and Engage: Revisit the pre/post analysis of the experience in your life where you identified behavior changes or new actions. What factors changed for you? What changed in the systems around you? Did your identity play a role? Did the culture of the place play a role? If so, how? Was power or privilege an asset or a barrier to this change at any time?

Diving in, Part 3: What role does behavior change play in creating new social norms that generate authentic and lasting change in communities?

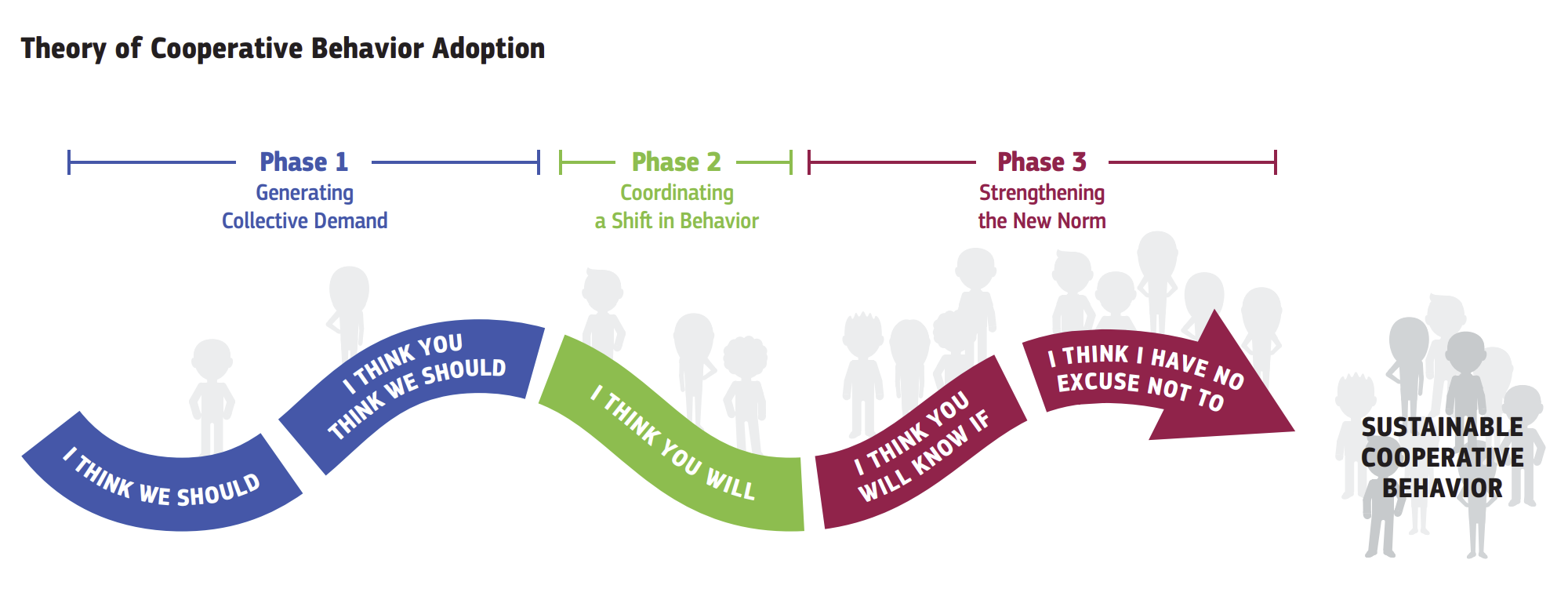

Global environmental, social and economic challenges are fundamentally people challenges. If we want to protect nature, communities, or economies, we need people to cooperate. Erik Thulin, Behavioral Scientist at Rare, shares a three-step process for applying psychological insights to overcome the challenges we face in acting cooperatively, so humanity and nature thrive.

View and Engage:

Many of the challenges involving both humans and the environment are cooperative dilemmas. While these dilemmas take on many names, such as public goods problems, tragedies of the commons, and common pool resource problems, the underlying dynamic is the same: the action that is best for the individual is different than that which is best for the group. Erik Thulin’s Ted Talk summarizes the theory of Cooperative Behavior Adoption, visualized by rare in their Cooperative Behavior Adoption Guide below:

Review and Engage: What drives community level change? What’s the role of individual actions? How might this strategy for cooperative behavior adoption change differ in rural communities versus cities or in the United States versus a developing island nation? Think of a challenge in a community in which you have lived where the initial demand for change was there. Did individual actions lead to lasting change? Find or develop and share a case study.

Outcomes:

Now that you have completed this module you should be able to:

Identify sustainable behaviors with a large environmental impacts.

Frame potential actions to be more inclusive and applicable in a local and global context.

Analyze a life experience and connect your actions to knowledge, identity, culture, power, or privilege.

Assess and share a community case study where changing behaviors was a goal for the common good.

Further Reading:

Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment and the Human Project by David W. Orr https://islandpress.org/books/earth-mind

Citation for this page: Lyons, L., Brandauer, S., & Sandiford, N. (2024). Sustainable Actions and Communities. In Hartman, E., Brandauer, S. & Sandiford, N. (Eds.). Interdependence: Global Solidarity and Local Actions. The Community-based Global Learning Collaborative. Retrieved from: https://www.cbglcollab.org/sustainable-actions-communities

Citations:

Larson, Gary. Far Side.

Pappas, E. & Pappas, J. (2015). The Sustainable Personality: Values and Behaviors in Individual Sustainability. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), 12-21. http://www.sciedu.ca/journal/index.php/ijhe/article/view/5858

Subhadra. (2017). Top 5 Inspiring Quotes By Mahatma Gandhi We Can Still Relate To. Retrieved from: https://www.dissdash.com/2017/10/02/top-5-inspiring-quotes-by-mahatma-gandhi-we-can-still-relate/

Rare and California Environmental Associates. (2019). Changing Behaviors to Reduce U.S. Emissions: Seven Pathways to Achieve Climate Impact. Arlington, VA: Rare.

Global Footprint Network. (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.footprintcalculator.org/

Global Footprint Network. (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.footprintnetwork.org/our-work/ecological-footprint/

Thulin, E. (2020). Cooperative Behavior Adoption Guide: Applying Behavior-Centered Design to Solve Cooperative Dilemmas. Arlington, VA: Rare.

Videos

Global Footprint Network. (2016, March 8). National Footprint Accounts – Ecological Balance Sheets for 180+ Countries. Retrieved From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_T5M3MiPfW4&feature=youtu.be

Freethink. (2019, September 12). The Sustainable City of the Future: Copenhagen, Denmark. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUbHGI-kHsU

World Bank. (2020, February 19). Output-based Aid Subsidies Provide Sustainable Sanitation and Water Services in Nairobi. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W7I7lgv5n0Y

Rare. (2020, February 11). Saving Nature With Behavioral Science | Erik Thulin | TEDxCambridgeSalon. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/Olv5LVIyjk4